The acceptable quality limit (AQL)—also called the acceptance quality limit—is the risk-based quality limit you use to decide, from a sample, whether a production batch meets your quality requirements.

AQL plays a central role in today’s product inspection cycle:: from incoming to in-process to final inspections, it gives buyers, suppliers, and inspectors a common language for quality control. Practically, AQL is best executed by experienced third-party teams as part of full product inspection services—they bring calibrated tools, documented sampling inspections, and unbiased decision making that protects your brand and the end user while controlling inspection costs.

In this article, you’ll see exactly how AQL works in practice: the sampling standards behind it (ISO 2859-1 / ANSI/ASQ Z1.4), how inspection levels (General I/II/III and Special S-1–S-4) set sample size, and how critical defects, major defects, and minor defects map to an acceptance number and rejection number.

You’ll also learn how AQL tables translate lot size into a sample size code letter, how OC curves quantify producer’s/consumer’s risks, when to apply switching rules, and which industries adapt AQL for their products.

What is the acceptable quality limit (AQL)?

AQL, per ISO 2859-1, is the worst tolerable process average used in attributes acceptance sampling to control lot disposition via a defined sampling plan.

Under the plan’s operating characteristic (OC) curve, lots at the AQL have ~95% probability of acceptance (α≈0.05).

You specify separate AQL values by defect class—e.g., 0% critical, 2.5% major, 4.0% minor in consumer goods; regulated goods may use ≤0.65% major and 0.1% or 0.065% critical.

AQL is a planning parameter, not “the percentage you allow in the sample.” The acceptance numbers in AQL tables come from binomial/Poisson mathematics selected to hit target α/β risks across many production runs. You then compare the number of observed defects in your sample size with the Ac/Re values to decide whether to accept or reject the batch

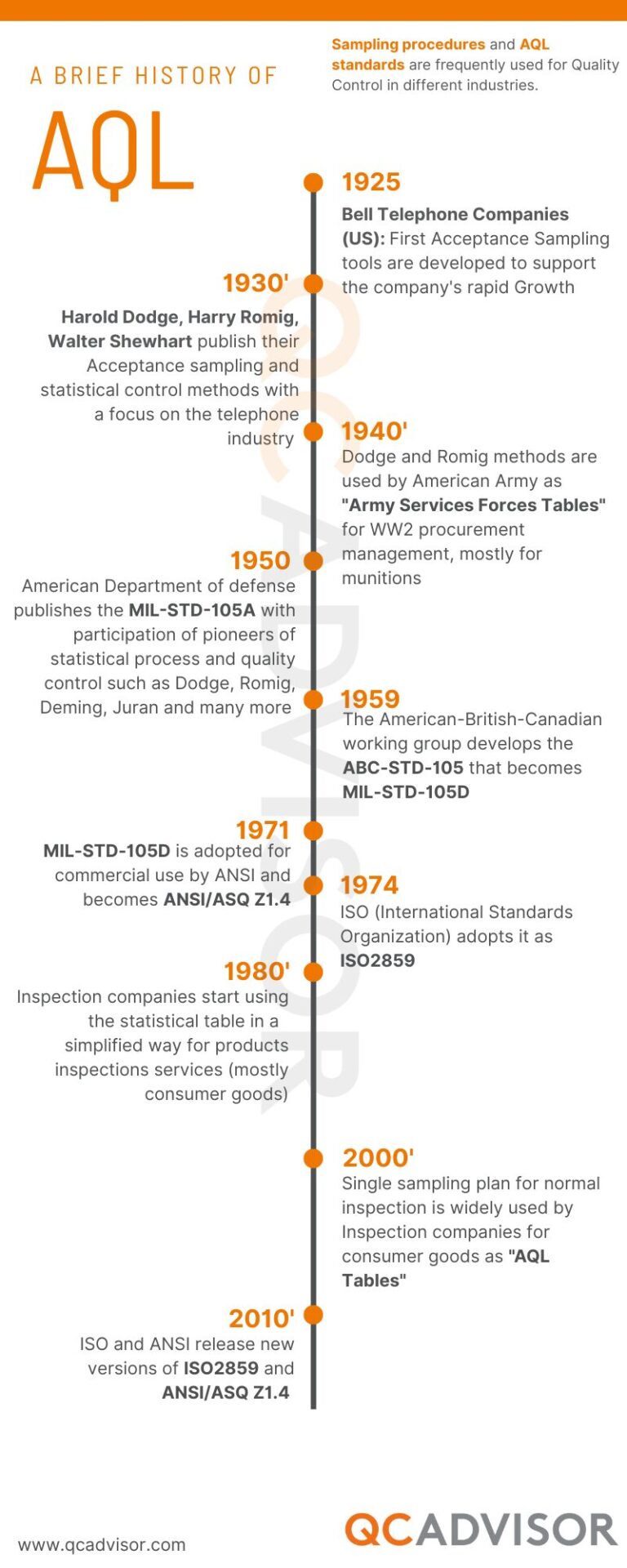

When was AQL first developed?

AQL’s roots trace to Bell Labs in the 1930s, when Harold F. Dodge and H. G. Romig developed acceptance sampling for mass production.

During World War II, method was adopted for large-scale U.S. military procurement and eventually formalized as MIL-STD-105, which harmonized with ANSI/ASQ Z1.4 and ultimately informed today’s ISO 2859-1.

Gradually, the terminology changed from“acceptable quality level” to “acceptance quality limit” to emphasize that AQL is a limit, not a target. Many sectors kept lineage variants—e.g., food programs referencing Codex STAN 233.

The modern ecosystem includes OC curves, switching rules (normal/tightened/reduced), and consistent sample size logic that buyers, suppliers, and quality assurance teams can apply to global supply chain decisions.

Aql History

What are the benefits of using AQL?

AQL improves objectivity, reduces cost versus 100% inspection, aligns expectations, and strengthens supplier governance. Six key advantages include:

- Quantify risk: Calibrate producer’s risk near 5% at AQL and consumer’s risk near 10% at RQL/LTPD; decisions rely on defined probability, not guesswork.

- Reduce effort: Typical sample size (e.g., code K n=125 or L n=200) inspects a fraction of the lot, cutting time versus 100% checks.

- Align stakeholders: Common defaults (0/2.5/4.0) are widely understood across exporters and manufacturers, speeding decision making.

- Support clarity: Clear acceptance criteria (e.g., n=125 at 2.5% → Ac7/Re8) prevents disputes.

- Scale economically: Sample size and acceptance increase sub-linearly with lot size, avoiding crude “inspect 10%” rules.

Enable governance: Works for incoming, in-process, and final quality inspections, and supports switching rules for stability or escalation.

How does acceptable quality limit (AQL) work?

You start by selecting your lot size, inspection level (I/II/III or S-levels), and AQL values by defect class; look up a code letter; read the sample size and acceptance number/rejection number; then count defects and decide.

Technically, the plan’s OC curve defines alpha (producer’s risk) and beta (consumer’s risk) across many lots.

Examples anchor the mapping: Lot 1,500 → code K → n=125; Lot 3,201–10,000 → code L → n=200; Lot ~15,000 → code M → n=315. Typical acceptance limits under normal inspection, Level II:

- n=125 at AQL 2.5% (major) → Ac7/Re8

- AQL 4.0% (minor) → Ac10/Re11

- n=200 at 2.5% → Ac10/Re11; at 4.0% → Ac14/Re15.

- n=315 at 2.5% → Ac14/Re15; at 4.0% → Ac21/Re22.

For a 50,000 lot at Level II and AQL 2.5%, n≈500 with roughly Ac21/Re22 (single-sample attributes plan). In Table 2, arrow cells show when to adjust a plan up or down to keep target risks at boundaries. RQL/LTPD sets the “bad” level; the IQL (indifference quality level) lies between AQL and RQL.

How do the AQL tables function, and what standards are they based on?

AQL tables implement ISO 2859-1 / ANSI/ASQ Z1.4 single-sample plans under normal inspection, mapping lot size and inspection level to a sample size code letter, then to sample size and Ac/Re at chosen AQLs.

Historically, they descend from MIL-STD-105; food programs may use Codex STAN 233 variants.

Table 1 provides the sample size code letter (e.g., K, L, M).

Table 2 converts that code into n and lists AQL columns (0.0 / 0.65 / 1.0 / 2.5 / 4.0 / 6.5) with acceptance numbers.

- General Inspection Levels I/II/III scale n (II is the default; I is smaller; III is larger).

- Special Inspection Levels S-1..S-4 yield very small n for targeted or destructive tests.

Anchors:

- Code L → n=200;

- at 2.5% major → Ac10/Re11;

- at 4.0% minor → Ac14/Re15. Code M → n=315;

- at 2.5% → Ac14/Re15

- at 4.0% → Ac21/Re22.

ISO 2859-10 discourages ad-hoc “inspect x%” because risks are undefined. In Codex STAN 233, smaller n and net-weight/content checks reflect destructive opening.

All of this keeps quality control processes consistent across industries, companies, and manuals.

Once you understand how AQL tables link inspection levels and acceptance criteria to specific sample sizes, the next step is to see how lot or batch size directly influences those calculations.

What is the lot or batch size?

The lot (batch) size is the count of homogeneous units presented for sampling and a single accept/reject decision.

In this context, mixed SKUs are separate lots.

The lot size defines which sample size code applies in Table 1 and thus n in Table 2.

Examples (General Level II):

- 1,201–3,200 → code K

- 3,201–10,000 → code L

- 10,001–35,000 → code M

A 1,500-unit lot (one SKU) yields code K → n=125; ~8,000 units → code L → n=200; 15,000 units → code M → n=315.

For in-process checks before completion, many practitioners size the lot as the quantity ready (e.g., 50,000 ready → n=500).

Proper carton dispersion (see FAQ) improves representativeness across cartons and positions.

What is the inspection level?

The inspection level specifies how intensively you sample under the standard. General I/II/III set broad effort:

- Level I (smaller n) for lower risk or trusted suppliers;

- Level II (default) balances cost and detection;

- Level III (larger n) for higher risk, new tooling, or complaint histories

- Special S-1 to S-4 use small sample sizes for focused checks (e.g., packaging dimensions, label legibility, destructive tests).

Example with lot 1,500: Level I → n=50; Level II → n=125; Level III → n=200. You might run S-1 (n=5) on outer-carton measurements while keeping workmanship at General Level II. Choose levels by risk exposure and the cost-of-inspection vs cost-of-failure trade-off.

What are the AQL limits?

AQL limits are the selected quality level parameters—by defect severity—that drive acceptance numbers in Table 2.

Typical consumer defaults: 0% critical, 2.5% major, 4.0% minor.

Stricter programs may apply 1.0% or 0.65% for major in high-reliability electronics; medical/pharma often set critical at 0.1% or 0.065%.

Example mappings under Level II:

- n=125 → 2.5% Ac7/Re8

- 4.0% Ac10/Re11. n=200 → 2.5% Ac10/Re11

- 4.0% Ac14/Re15. n=315 → 2.5% Ac14/Re15

- 4.0% Ac21/Re22.

Remember, acceptance numbers don’t equal the AQL percentage of n; the plan controls α (producer’s risk) and β (consumer’s risk) across multiple lots, rather than reflecting a single-sample proportion

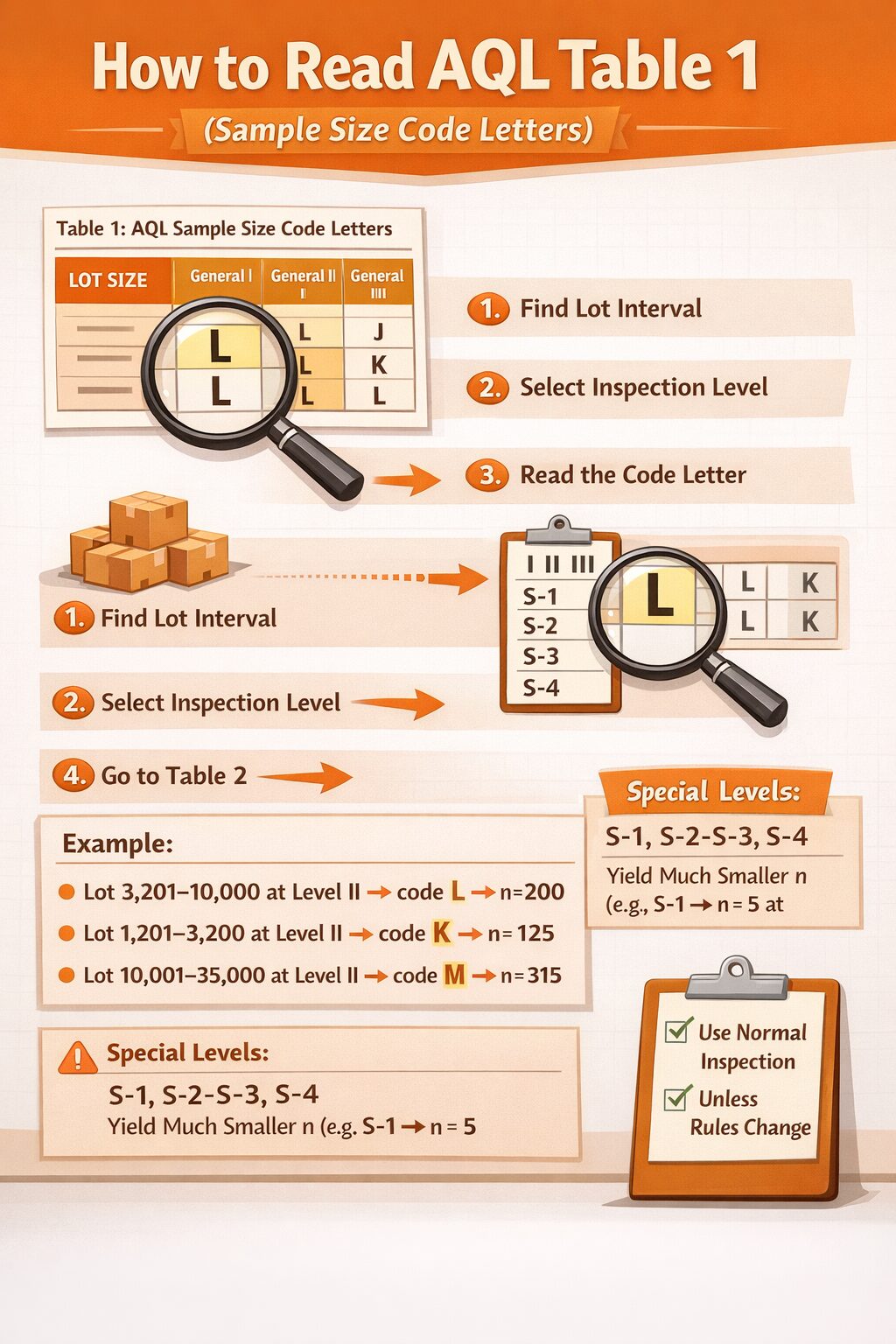

How do you read AQL Table 1 (sample size code letters)?

You read AQL Table 1 by locating your lot size row and chosen inspection level column to obtain the sample size code letter, which you’ll carry to Table 2 to find sample size and acceptance criteria.

Here are the four main steps:

- find the lot interval

- select General I/II/III or Special S-1..S-4

- read the code letter

- go to Table 2 to get n and Ac/Re.

For example:

- Lot 3,201–10,000 at Level II → code L → n=200.

- Lot 1,201–3,200 at Level II → code K → n=125

- Lot 10,001–35,000 at Level II → code M → n=315

Special levels yield much smaller n (e.g., S-1 can be n=5 at 1,500 units).

Use normal inspection unless switching rules require a tightened or reduced level.

How To Read Aql Table 1

Compact reference (excerpt):

- 281–500 → G/I=E, II=F, III=G

- 501–1,200 → H/I=G, II=H, III=J

- 1,201–3,200 → K (Level II)

- 3,201–10,000 → L (Level II)

- 10,001–35,000 → M (Level II)

With the code letter from Table 1 in hand, you can use Table 2 to find the exact sample size and acceptance numbers for making lot decisions

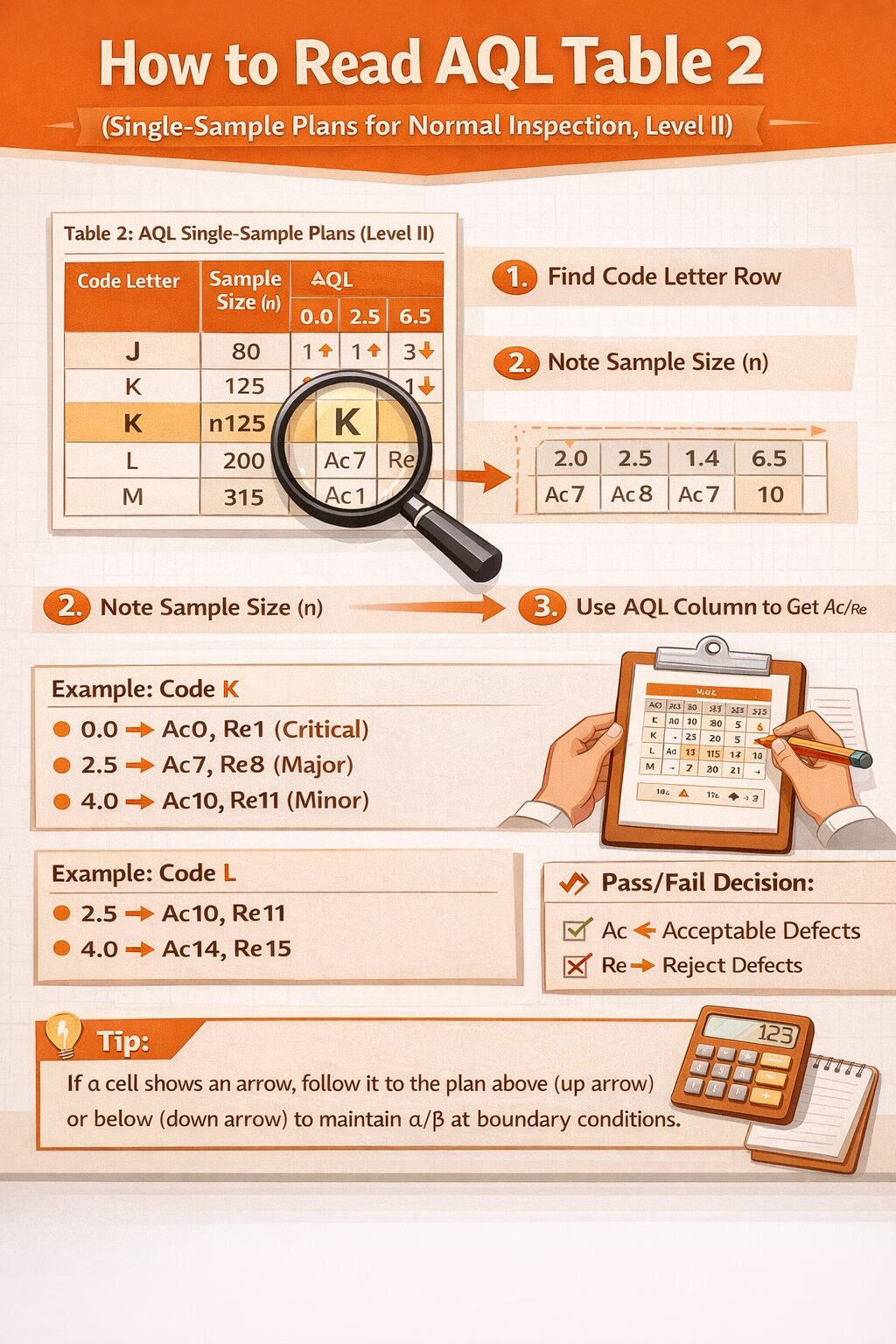

How do you read AQL Table 2 (single-sample plans for normal inspection, Level II)?

You read AQL Table 2 by finding the row for your code letter, noting the sample size (n), then using the AQL column (e.g., 0.0, 1.0, 2.5, 4.0, 6.5) to get Ac/Re and decide pass/fail per defect class.

- Code K (n=125): AQL 2.5 → Ac7/Re8 (major);

- AQL 4.0 → Ac10/Re11 (minor);

- AQL 0.0 → Ac0/Re1 (critical). Code L (n=200): 2.5 → Ac10/Re11;

- 4.0 → Ac14/Re15. Code M (n=315): 2.5 → Ac14/Re15; 4.0 → Ac21/Re22.

When a cell shows an arrow, follow it to the plan above (up arrow) or below (down arrow) to maintain α/β at boundary conditions.

How To Read Aql Table 2

What happens when you land on an arrow in Table 2?

When you land on an arrow in Table 2 follow the arrow immediately: up arrow → use the plan above; down arrow → use the plan below.

The tables place arrows at discrete breakpoints so that alpha/beta risks remain smooth as you cross lot size or AQL boundaries.

Example: a small-n boundary (e.g., a code E row near AQL 2.5%) with a down arrow directs you to inspect n=20 with an appropriate Ac/Re such as Ac1/Re2 in that region—preventing step-changes that would distort decision risks.

Which inspection levels should you choose and why?

Start at General Inspection Level II for most consumer goods because it balances detection and throughput.

Move to Level III for higher risk (new supplier, customer complaints, new tooling) and down to Level I for trusted suppliers and low-hazard items.

Use Special levels (S-1..S-4) for targeted, time-intensive, or destructive checks while keeping workmanship at a General level.

With lot 1,500, the throughput trade-off is visible: Level I → n=50, Level II → n=125, Level III → n=200.

S-levels may reduce a packaging test to n=5–32 while you still inspect workmanship at General Level II.

Align level choice with potential harm, brand impact, warranty exposure, and inspection costs. Products from high-end brands or those that are safety-critical require stricter sampling.

What are the General Inspection Levels (I, II, III)?

General levels define the sampling intensity for overall workmanship and functional checks.

- Level I lowers sample size for cost control when processes are stable

- Level II is the standard (better discrimination at reasonable effort)

- Level III increases n for maximum detection. At the same lot size (e.g., 1,500 units), n might swing from 50 (I) to 125 (II) to 200 (III).

Choose III if recent failures or new tooling raise risk; choose I for cost savings after SPC shows stability and customer expectations are met.

What are the Special Inspection Levels (S-1 to S-4)?

Special levels provide very small samples to cover focused or limited-scope inspections—useful when tests are destructive, slow, or peripheral.

Examples:

- S-1 for outer-carton width/dimensions

- S-2/S-3 for slow function tests

- S-4 for moderate effort

For a 1,500-unit lot, S-1 can be n=5. Keep General Level II for workmanship to protect product quality while applying S-levels for packaging, labeling, or power-cycle tests that would otherwise consume units.

How do you calculate and apply AQL using the tables?

At a high level, you define the lot, select inspection level, pick AQLs, find the code letter in Table 1, then read n/Ac/Re in Table 2 and inspect randomly.

There are six main steps:

1) Define lot & defect classes (H3)

Fix lot size and defect taxonomy (critical/major/minor) for consistent quality assessment.

2) Choose inspection severity & level (H3)

Default to normal inspection, General Level II; escalate or reduce via switching rules.

3) Select AQLs by class (H3)

Typical defaults: 0/2.5/4.0; tighten for high hazard or stricter customers.

4) Read code letter in Table 1 (H3)

Map lot size × inspection level → code letter (e.g., L for 5,000 at Level II).

5) Read n and Ac/Re in Table 2 (H3)

Find sample size and acceptance number; note arrows and boundary rules.

6) Inspect randomly and decide (H3)

Randomly select samples across √cartons (often +1); tally defect levels; compare to Ac/Re; document.

Worked example 1 (consumer product, AQL 2.5 major/4.0 minor)

Decision first: Lot 1,500, Level II, code K → n=125.

With AQL 2.5/4.0, the plan is Ac7/Re8 (major) and Ac10/Re11 (minor); critical 0.0% → Ac0/Re1.

If you find 6 major + 9 minor, the lot passes; 8 major or 11 minor means fail; any critical defects means fail.

Pull samples across √cartons (+1)—e.g., 100 cartons → select 11 cartons to improve representativeness.

Worked example 2 (regulated product, AQL 0.65 major/0.1 critical)

Decision first: Lot 5,000, Level II, code L → n=200. With critical 0.1%, use Ac0/Re1; with major 0.65%, typical Ac2/Re3–Ac3/Re4 depending on the exact cell; minor could be 1.5–2.5%.

Such aql inspection choices account for stricter safety requirements; if failures cluster, switch to tightened severity per the standard’s switching rules and document containment and traceability actions before shipment.

What is an AQL calculator or sampling simulator, and when should you use one?

An AQL calculator is a tool that automates sample size selection, acceptance numbers, and sometimes OC curve visualization from ISO 2859-1/ANSI Z1.4 inputs.

Use it for large portfolios, training, and “what-if” cases when manual table lookup slows work. .

AQL Sample Size & Acceptance Calculator

Enter your lot size, inspection level, and AQLs by defect class. The sampling plan will appear below once the required fields are filled.

Why do quality programs rely on AQL instead of 100% inspection?

Because AQL delivers risk-based objectivity at manageable cost while 100% inspection suffers from fatigue and error.

Even so-called “100%” screens often detect ~80% of issues in practice. With n=125–315 you preserve throughput while bounding risks with known OC curves; after a failed lot, you can still order a 100% sort to salvage inventory.

AQL therefore protects product quality and customer satisfaction without crippling the production line or budget.

What are the defect categories and typical AQL levels?

AQL plans separate defect type into critical, major, and minor, then assign AQL limits that reflect hazard, function, and cosmetic expectations.

Typical consumer ranges: critical 0.0% (some sectors 0.1% or 0.065%), major 0.65–2.5%, minor 1.0–4.0% (occasionally up to 6.5% for commoditized items). Regulated and safety-critical sectors use stricter limits.

Critical defects

Definition: safety, regulatory, or legal risk; unacceptable for the end user. Typical AQLs: 0.0% in most programs; regulated contexts may set ≤0.1% or 0.065%.

Examples:

- battery leaks

- toxic substances

- incomplete sterilization

- sharp edges causing injury

- electrical hazards

Major defects

Definition: likely to result in product failure, malfunction, or returns. Typical AQLs: 0.65–2.5%; premium/luxury goods often target ~1.0%.

Examples:

- malfunctioning controls

- structural weakness

- wrong labeling that affects use

- noticeable color mismatch.

Minor defects

Definition: cosmetic or usability deviations that don’t materially affect saleability. Typical AQLs: 2.5–4.0%; certain decorative features lower AQL to 1.0%.

For example:

- small scratches

- slight color variance

- superficial stitching issues in a clothing manufacturer context.

How should you select AQL levels for your product and risk appetite?

Begin with hazard assessment: any safety or regulatory exposure → 0.0% critical (or ≤0.1% for highly regulated).

For electronics, consider 0.65–1.0% major on critical subassemblies; for apparel, 2.5% major / 4.0% minor is common.

Calibrate by brand promise, market positioning, warranty risk, and customer tolerance.

H3 What do common AQL values such as 2.5 mean?

AQL 2.5 is a quality limit parameter of the sampling plan, not “2.5% of the sample may fail.” At n=200, Ac10 (not 5) is typical; at n=125, Ac7.

Its meaning derives from the plan’s OC curve: it sets the probability of acceptance across many lots, it does not represent a fixed percentage within a single sample.

Which sampling methods are used with AQL, and how do you choose among them?

AQL supports single, double, and multiple/sequential sampling methods.

Single is default for simplicity. Double can reduce average n when lots are clearly good or bad. Multiple/sequential further trim average n but add administrative complexity.

Choose by lot history, urgency, inspection costs, and desired OC-curve characteristics.

Single-sampling plans

A single sample of size n is drawn; you accept if defects ≤ Ac and reject if defects ≥ Re. It’s the simplest approach, fastest to train, and standard for normal inspection in most quality control methods.

Double-sampling plans

Two stages: inspect n1; if results are inconclusive (between accept/reject bands), inspect n2 and combine counts. Reduces average units inspected when quality is consistently good or bad.

Multiple or sequential sampling

Stage-wise or sequential pulls with early accept/reject boundaries minimize expected sample sizes. Best when inspection level effort is expensive and you can manage plan administration.

How do you choose the right sampling method?

Prefer single for routine products and straightforward quality assurance. Use double when lots are stable and you want lower average sample size.

Use sequential sampling when tests are slow, destructive, or time is limited. Larger lots and high risk justify methods with steeper OC curves (bigger n or lower c).

How does AQL handle statistical risks and operating characteristics?

AQL plans define decision risks through OC curves: at the AQL, α≈0.05 (producer’s risk of rejecting a good lot); at an RQL/LTPD, β≈0.10 (consumer’s risk of accepting a bad lot).

Random sampling helps reduce bias; increased sample size steepens the OC curve, improving discrimination between acceptable and unacceptable defect rate levels.

What are operating characteristic (OC) curves?

An OC curve links % defective to probability of acceptance for a plan. For illustration, with n=200, you might see P(accept) around high-90s at 1%, dropping steeply by 3%, approaching near-zero by 10% for tight acceptance number choices.

How does sample size affect the OC curve?

Larger n makes the curve steeper—your plan is more decisive, shrinking the indifference region and strengthening protections for both producer and consumer.

How does the acceptance number affect the OC curve?

Lower c (smaller maximum number of defective allowed) shifts the curve left, reducing consumer’s risk but raising producer’s risk; higher c does the opposite.

What are producer’s risk (alpha) and consumer’s risk (beta)?

Alpha (α) is the risk of rejecting a lot that truly meets the AQL (~5%). Beta (β) is the risk of accepting a lot at the rejectable quality level (~10%). Plans balance these to achieve program goals.

How does random sampling improve representativeness?

Randomization avoids selection bias. Spread pulls across cartons using √cartons (often +1); some programs use 2×√cartons. Stratify by page of the menu of cartons (positions in the stack), color or size variants when applicable, and timing within the production process.

How do severity switching rules (normal, tightened, reduced) work?

Switching rules adapt normal inspection to tightened (stricter) or reduced (lighter) severity according to recent results.

Most programs start at normal; repeated problems trigger tightened; sustained good performance allows reduced—controlling risks without rewriting the aql system.

When does Normal switch to Tightened?

After a specified pattern of rejections or quality signals indicating deterioration—record triggers in your SOP and notify suppliers.

When does Tightened switch to Normal?

After consecutive accepted lots that meet criteria; maintain records to prove recovery.

When does Normal switch to Reduced?

When lots show consistent compliance over multiple cycles and processes remain stable; ensure compliance and traceability continue.

When does Reduced switch to Normal?

At the first rejection sign, changes in process, or adverse updates in the field; revert immediately to protect consumers.

Who uses AQL and in which contexts is it applied?

Buyers, suppliers, and third-party inspectors use AQL for incoming, in-process, and final quality inspections across components, subassemblies, finished goods, and even non-product checks where items are classed as OK/defective.

Logistics affect carton dispersion so sample size covers the supply chain fairly.

Which roles rely on AQL?

Buyers set quality requirements and AQLs. Suppliers prepare compliant lots and records and third-party inspectors execute the sampling process, tally defects and issue reports for decisions.

AQL is always used to determine sample sizes for product inspections.

Can AQL be used for incoming inspections of components?

Yes. Use a tighter AQL for critical defects and apply Special levels for destructive checks. Calibrate by downstream risk: high-impact parts justify Level III or lower majors (e.g., 0.65–1.0%).

Which standards define AQL, and how do attributes and variables sampling differ?

AQL for attributes sampling is defined by ISO 2859-1 (globally) and ANSI/ASQ Z1.4 (U.S. equivalent), with lineage from MIL-STD-105E

ISO 3951 defines variables sampling (using measured values and standard deviations). Some sectors cite Codex STAN 233 (foods) and FDA-specific plans (e.g., 21 CFR 800.20 for medical gloves).

Attributes sampling marks each unit as defective or non-defective and fits visual or functional checks

Variables sampling uses measurements to achieve the same OC curve with generally smaller n, assuming normality and capable process statistics.

Regulators may prefer ISO 16269-6 or capability indices (Cp/Cpk) for process validation, while AQL remains appropriate for lot acceptance and shipment release.

How should AQL be applied across industries and regulatory standards?

AQL applies broadly, but industry standards and regulations tune the numbers. Legal or customer requirements override defaults.

- Medical/pharma: critical ≤0.1% (often 0.065%); auditors may prefer capability evidence for validation beyond AQL.

- Food & beverage: Codex STAN 233 uses smaller sample size and net-weight checks (destructive).

- Electronics: tighter major (e.g., 0.65–1.0%); function first.

- Textiles/apparel: 2.5% major / 4.0% minor, with strong cosmetic criteria.

H3 Manufacturing and electronics

Use 0.65–1.0% for major on critical subassemblies; 2.5% for general assemblies; minor 4.0%. Focus on function, solder quality, safety.

H3 Pharmaceuticals and medical devices

Align with GMP/ISO 13485; set critical ≤0.1% (often 0.065%). Recognize that some auditors expect capability studies (ISO 16269-6, Cp/Cpk) for validation; AQL remains for lot release. FDA 21 CFR 800.20 provides glove-specific sampling.

H3 Textiles and apparel

Cosmetic standards dominate; 0.0% critical, 2.5% major, 4.0% minor typical. Emphasize color, size, seam and stitch integrity.

H3 Food and beverage (including Codex STAN 233)

Smaller n with weight-based tables due to destructive opening; critical defects remain 0.0% for safety.

H3 What legal or customer requirements should be considered?

Retailer quality manuals, OEM contracts, and regulatory constraints can set stricter AQL and sampling method rules (e.g., FDA glove sampling). Always honor contractual acceptance criteria.

How does AQL compare with SPC, Six Sigma, TQM, and Zero Defects?

AQL is a lot acceptance gate; SPC monitors process stability; Six Sigma reduces variability; TQM is organization-wide culture; Zero Defects is a philosophy. They’re complementary: many programs use SPC upstream and AQL downstream, while Six Sigma targets reduction in defect rate beyond what acceptance sampling alone can achieve. Six Sigma aims at ~3.4 DPMO; AQL plans accept bounded risks (α≈5%, β≈10%).

AQL vs Statistical Process Control (SPC)

AQL decides shipment acceptance; SPC prevents defects by controlling the production process in real time.

AQL vs Six Sigma

AQL classifies lots pass/fail; Six Sigma uses DMAIC and capability metrics to reduce defects permanently.

AQL vs Total Quality Management (TQM)

AQL is a gate; TQM embeds quality into every function, policy, and metric.

AQL vs Zero Defects

AQL tolerates bounded risk; Zero Defects aspires to none, practical where automation and error-proofing eliminate human miss.

When should you transition away from AQL?

When SPC is mature, automation is robust, and traceability strong, you can reduce reliance on acceptance sampling—except where regulations still require it.

How do you implement AQL in your quality system?

Implementation follows governance, procedures, training, tools, pilots, and continuous review. There are 10 steps:

1) Assess risk & objectives (H3)

Map hazards, customers, and quality limit aql needs.

2) Define scope (H3)

Decide which products and components use AQL.

3) Select AQLs (H3)

Set critical/major/minor per risk tiers.

4) Author SOPs (H3)

Define defect limits, counting rules, carton dispersion.

5) Train teams (H3)

Calibrate inspectors; align terms and taxonomy.

6) Choose tools (H3)

Tables, aql calculator, checklists, photo capture.

7) Pilot lots (H3)

Verify interpretation and handoffs.

8) Roll out (H3)

Apply normal inspection; track results.

9) Apply switching rules (H3)

Move tightened/reduced per history.

10) Review & improve (H3)

Audit data; close loops with suppliers.

Steps to introduce AQL

Establish governance, write SOPs, train, publish sampling plan table presets, and audit execution loops with root-cause and corrective actions.

Three practical tips for using AQL effectively

Use risk-tiered AQLs; stratify sampling across √cartons (+1); and don’t negotiate post-fail—keep credibility by following the plan.

Common challenges and how to overcome them

Tackle misclassification with photo-rich libraries, poor randomization with strict carton rules, and supplier pushback with clear contracts and shared industry experts references.

Best practices for sustainable AQL deployment

Maintain data discipline, instrument calibration, sample traceability, and feedback loops to upstream production.

What factors determine lot acceptance or rejection under AQL?

Decisions depend on sample size (n), acceptance numbers (Ac) by class, and your tallied defects. Rule of thumb: if (critical > 0) → fail; if (major > Ac_major) or (minor > Ac_minor) → fail; else accept. Document counts, photos, units, and carton coverage.

How do you determine sample size and acceptance number?

Use Table 1 for code letter and Table 2 for n and Ac/Re (cross-check with an aql calculator). Example: L → n=200; AQL 2.5 → Ac10; AQL 4.0 → Ac14.

How do you categorize defects and tally counts?

Define critical/major/minor with examples and counting rules. Decide in policy whether multiple minors on one unit escalate to one major; the standard is silent—pick a rule and apply it consistently.

Can you combine different inspection levels or tests for one lot decision?

Yes, but standards don’t define aggregation. Set governance upfront—for example, workmanship at Level II and dimensions at S-3, with “any fail → lot fail” or weighted criteria.

When should AQL be used, and what are its limitations and alternatives?

Use AQL for lot acceptance in supplier management, final QC, and shipping decisions. Limitations: it evaluates lots, not continuous process stability; it can accept bad lots or reject good ones; and it requires resources across many suppliers. Alternatives and complements include SPC, capability metrics (Cp/Cpk), sequential sampling, and automated in-line checks.

What are the main limitations and criticisms of AQL?

AQL has downsides. There are 6 disadvantages:

- Do not improve processes by themselves—only classify.

- Do not eliminate sampling error; α/β always exist.

- May allow consumer risk near 10% at RQL/LTPD.

- Encourage post-production detection instead of prevention.

- Permit subjectivity in defect classification without strict SOPs.

- Increase staffing/logistics burden across many suppliers.

What are credible alternatives to acceptance sampling?

For validation, regulators often prefer ISO 16269-6 analyses and capability indices; for prevention, deploy SPC, automated inspection, continuous sampling, or targeted 100% inspection where economics and risk justify it.

How much does an AQL inspection cost?

In the U.S., third-party AQL inspections typically range from $280–$450 per inspector-day, plus travel if remote regions are involved. There are 6 cost factors:

- Location & travel: access and distance raise expenses.

- Inspection scope & levels: Level III or multiple S-levels increase time.

- Sample size (n): 200 vs 125 means more unit checks.

- Inspector day-rate: varies by market and experience.

- Reporting & evidence: photos, measurements, and rework verification add hours.

- Re-inspection: after a fail, re-inspection is usually supplier-funded per contract.

Frequently asked questions about AQL

Do you have to accept some defects under AQL?

No—AQL is a limit, not authorization. Acceptance follows Ac/Re rules; residual risk remains by design, and ISO notes AQL is not a “desirable” quality level.

Should buyers charge suppliers for defective units found?

If the lot passes, many programs avoid charge-backs and focus on corrective actions. If it fails, suppliers typically sort/rework and pay re-inspection per contract.

What happens if the AQL limit is exceeded?

The lot is rejected; initiate containment, 100% sort or rework, and then schedule re-inspection under the same plan.

Can I design my own sampling plan instead of ISO 2859/ANSI Z1.4?

Yes—use binomial/hypergeometric models (e.g., Minitab/Excel) to match desired OC curves; secure stakeholder agreement in advance.

Is AQL only one standard?

No: ISO 2859-1 / ANSI Z1.4, MIL-STD-105E, and ISO 3951 (variables) coexist; Codex STAN 233 applies in foods.

Why not inspect a fixed percentage (e.g., 10%) instead of using AQL?

Fixed-% sampling yields unknown risks; AQL tables set defined α/β and better discrimination.

Why don’t the accept numbers match the AQL percentage I selected?

Because Ac/Re arise from probability models to meet α/β across many lots. Example: 2.5% with n=200 → Ac10, not 5.

What happens when I land on an arrow in Table 2?

Use the indicated adjacent plan (up or down) to maintain target risks at boundaries.

How many cartons should samples be pulled from?

Select √cartons (often +1) at minimum; some use 2×√ for extra dispersion.

Can I apply the same AQL to all products?

No—tailor by hazard, user experience, brand, and industry standards.

What should I do to salvage a rejected lot?

Perform 100% sort/rework, document, and re-inspect; concessions require formal approval.

Is AQL still a valid approach today?

Yes—for lot acceptance. Pair it with SPC, automation, and continuous improvement upstream.

What did W. Edwards Deming say about acceptance sampling?

He favored prevention and sometimes 0 or 100% checks based on economics; AQL is still practical for importers managing diverse suppliers.

Which parts of the AQL standard are not defined and left to practitioners?

Defect taxonomy, combining multiple tests, and carton dispersion rules—set these in your SOP.

Does AQL guarantee zero defects to customers?

No; it bounds probability, not outcomes. Communicate residual risk clearly.